Candiotti article in 2023 Vancouver Canadians program

Posted by alifeofknuckleballs in Baseball, Baseball Biography, Blue Jays Baseball, Blue Jays Records, Knuckleballs on March 4, 2024

No copyright infringement is intended with this post. This was a piece that I submitted to the MiLB Vancouver Canadians in 2023, and the pages are courtesy of the ISSUU website.

I am merely posting this article here to share with others who love the knuckleball and Candiotti’s story.

New book on knuckleballs

Posted by alifeofknuckleballs in Baseball History, Knuckleballs on October 6, 2023

My new book on knuckleballs has now been published.

Every book that I’ve written is different. This one started before the COVID19 pandemic, and although I left it alone for a while (I wasn’t particularly motivated for a time), I finally decided to continue working on it the last few weeks and it was finally completed.

A lot of research went into this book (most of which came before the pandemic hit), and I’m very proud to have completed it.

This date in history: August 3, 1997 – Candiotti one-hits the Yankees

Posted by alifeofknuckleballs in Baseball, Baseball History, Indians Baseball, Indians Records, Knuckleballs, Low-hit Gems, Shutouts & Scoreless Streaks on August 4, 2022

August 3, 1987: Yankees 0, Indians 2

NYY 000 000 000 – 0 1 1

Cleve 110 000 00x – 2 6 0

W-Candiotti L-Trout

“The first time I came close to a no-hitter was against the Yankees, when I took a no-no into the eighth inning,” Candiotti recalls in a conversation for the book A Life of Knuckleballs. “But Mike Easler broke that one up and I ended up with a one-hitter.”

When Candiotti became only the 22nd pitcher since 1918 to toss a nine-inning one-hitter versus the Yankees, it turned out to be a big game. It would be the start of an ugly 3-10 slide that knocked the Yankees out of first place in the AL East.

Wait, you say. The Yankees in contention in the 1980s? Nah, can’t be true. Pure myth, right? Nobody in their right mind would consider the Yankees of that decade to be any good. It’s a well-known fact that they didn’t win any championships in the 1980s, and didn’t make the postseason in that decade after losing the ’81 World Series.

But it would be inaccurate to say the Yankees of that era weren’t any good. In the 1980s, they still had good hitters such as Dave Winfield, Don Mattingly, Willie Randolph, Rickey Henderson, and Don Baylor. Left-hander Ron Guidry was still in pinstripes—and would be until 1988—and had 20-win seasons in 1983 and 1985. The Yanks also had All-Star left-hander Dave Righetti, who began the decade as a dependable starter before becoming a star closer by the mid-1980s.

In 1985, the Yankees, who finished 97-64, went into their season-ending series against Toronto still with a shot at the AL East title, but were finally eliminated by losing their penultimate game. New York ended up with the league’s second-best record, trailing only the Blue Jays’ 99 victories. But in those days, with only two divisions and no wild card, the Yankees missed out on the postseason while the 91-win Kansas City Royals, champions of the West, took on Toronto in the ALCS.

In 1983, New York won 91 games but finished third, seven games behind the AL East-winning Orioles. In ’84, the Yankees again finished with enough wins to capture a division championship in the West. But their 87-75 record was good enough only for third in the East, while the Royals won the West with only 84 victories.

In 1986, the Yankees finished 90-72, second in the division, 5.5 games behind Boston. But they weren’t as close as the final standings indicated, as they were 10 games out with only 12 games to go. They won nine of those final 12 contests to reach 90 victories, including a meaningless four-game sweep at Fenway Park to close out the season, with the Red Sox having already clinched the division.

But 1987 seemed like a different year. Entering play on August 3rd, they had the AL’s best record at 64-41—that’s .610 baseball, a 99-win season over a full 162-game schedule—and were 2.5 games ahead of second-place Toronto. They’d just won six of their last seven games, including a big series victory over Detroit (the eventual division champion), and were in Cleveland for the start of a two-game series against the hapless Indians, who at 37-67 had baseball’s worst record.

That opener pitted left-hander Steve Trout—who was acquired from the Chicago Cubs on July 12th—against Candiotti. Trout had tossed back-to-back shutouts in his final two starts for Chicago before being dealt to New York. Though he hadn’t won a game yet in three Yankee starts, he’d looked good in his previous outing against Kansas City, tossing six shutout innings. Meanwhile, Candiotti was 3-11 on the season and had compiled a 5.09 ERA in five July starts.

But what do you know? Cleveland got ahead 2-0 after two innings, and Trout was gone in the fourth after throwing a two-out wild pitch. It was Trout who looked more like a knuckleballer, not Candiotti. Trout’s line: 3.2 innings, three hits, five walks, and three wild pitches. Yankees catcher Mark Salas was also charged with a passed ball, and—according to the Melville Newsday—there were four other pitches from Trout that bounced past him.

Ironically, the guy with the knuckleball had no such problems. Candiotti retired 21 of the first 22 Yankees—with only a second-inning walk to Winfield ruining his shot at perfection—taking a no-hitter into the eighth. Through seven innings, just one baserunner! And this was a lineup that had Mattingly, Winfield, Mike Easler, and Mike Pagliarulo (who’d smack 32 homers in 1987) in the 3-4-5-6 spots in the batting order.

Mattingly thought the key to Candiotti’s pitching was his knack for throwing strikes all evening. It didn’t matter what he was throwing, whether it was the knuckler, curve, or fastball. “He just got ahead in the count, batter after batter,” said Mattingly that night. “When you do that, you’ve got the freedom to throw the knuckleball all the time” (Michael Martinez, “Indians Blank Yankees on Candiotti’s One-Hitter,” Associated Press/New York Times, August 4, 1987).

Candiotti remembers he didn’t throw that many knuckleballs—only about 30-40 percent. “I mixed in my fastballs, slow curveballs, and changeups with the knuckler,” he says. “I threw more fastballs and curveballs than the knuckleball.” All of those pitches worked. After the walk to Winfield, Candiotti retired the next 18 batters in a row.

Alas, Easler led off the top of the eighth with a clean single to rightfield that broke up the no-no. It came on a 3-2 fastball that dropped in, just in front of charging centerfielder Brett Butler. “I fell behind 3-0 to Easler,” Candiotti recalls. “When the count was 3-1, he absolutely ripped a fastball 350 feet to rightfield which went just outside the foul pole. I was fortunate that it went foul. Now, with the count 3-2, I didn’t wanna walk him, so I threw him another fastball. It was a fastball, high and inside.”

Easler managed to get his bat on the pitch, hitting a weak little blooper that dropped in. “He just blooped a single to rightfield that fell no more than 12 feet in front of Butler,” Candiotti says. “Brett was charging hard for the ball but he couldn’t have gotten to it. It was hit too shallow for him, and too deep for [second baseman] Tommy Hinzo. It was just a little soft line drive that dropped in for a hit. No chance for anybody to get to it.”

Easler said afterward that he was looking for the fastball, and guessed right, knowing Candiotti couldn’t afford to walk him with the left-handed Pagliarulo on deck and the left-handed Dan Pasqua still on the bench. “I didn’t think I’d see a knuckleball with a 3-2 count,” Easler said. “We were down by two. You don’t want to put a guy on base and bring the tying run to the plate” (Marty Noble, “Candiotti Shows His Stingy Side,” Newsday, August 4, 1987).

But with the tying run indeed at the plate, Candiotti settled down and got three straight groundball outs to end the eighth. In the ninth, Henry Cotto struck out, Claudell Washington grounded out to second, and on a two-strike knuckleball, Gary Ward swung wildly and missed for the final out. Only two Yankees reached base, with Candiotti walking one, striking out five, and throwing 108 pitches.

Why did a good ballclub like the Yankees—a first-place team at the time—have so much trouble against him? “They had an aggressive club,” Candiotti says. “Their hitters liked swinging for the fences, and I guess when they faced pitchers that threw off-speed stuff, they didn’t do so well. If you had a pitcher that threw knuckleballs or changed speeds, you had a good chance of shutting them down.”

It was the start of the end for the ’87 Yankees, who at the time were the AL’s best team. Including the one-hitter, they’d lose 10 of their next 13 games—including another loss to Candiotti on August 14th—to fall out of first place for good, going from 2.5 games up to three games out during that slide. By season’s end, they’d finish in fourth place at 89-73, nine games out.

Was it because Candiotti’s knuckleballs put them into a slump?* He laughs. “Actually, like I said, I threw maybe 30-40 percent. I threw mostly knuckleballs to Mattingly and Winfield, though, because those two guys were the big bats in their lineup that could do the most damage. I used my other pitches also, so I had everything working that night.”

According to Candiotti, there was one upside that the no-hitter was gone. He no longer got the silent treatment when he returned to the dugout after the top of the eighth inning. “When a pitcher’s throwing a no-hitter, nobody in the dugout talks to him because they don’t wanna jinx him. It’s one of these baseball superstitions. So, for the longest time—maybe after the fourth inning—nobody said anything to me when I was on the bench. It felt very strange for me, because I’d never experienced it before. But when I got back to the dugout after the no-no was broken up, [pitcher] Scott Bailes came up to me and said, ‘Oh, good. Now I can talk to you.’”

Four weeks later, Candiotti came close to another no-hitter—and endured the silent treatment from his teammates in the dugout once again. Steve Trout, meanwhile, would be winless with the Yankees, going 0-4 with a 6.60 ERA in 14 appearances before being traded to Seattle in the off-season.

*In the 1988 season finale, Candiotti defeated the playoff-bound Red Sox, who then got swept by Oakland in the ALCS. Was it Candiotti’s knuckleball that put the Boston hitters in a slump? “Nah,” he laughs. “I think it was more the fact that they were facing Dave Stewart and Dennis Eckersley in the playoffs.”

Did You Know?

Two or fewer baserunners…

From 1970 to 2010, only seven Indians pitchers threw complete games in which they allowed two or fewer baserunners. (Candiotti’s was just the 15th since 1918.)

Pitcher / Date / Opponent / Result

Dick Bosman / Jul. 19, 1974 / Athletics / no-hitter/one baserunner

Dennis Eckersley / May 30, 1977 / Angels / no-hitter/one baserunner

Dennis Eckersley / Aug. 12, 1977 / Brewers / one-hitter/two baserunners

Len Barker / May 15, 1981 / Blue Jays / perfect game

Tom Candiotti / Aug. 3, 1987 / Yankees / one-hitter/two baserunners

Tom Kramer / May 24, 1993 / Rangers / one-hitter/one baserunner

Billy Traber / Jul. 8, 2003 / Yankees / one-hitter/one baserunner

No pitcher has ever thrown a perfect game against the Yankees. But Candiotti’s “nearly perfect” game made him just the 10th major-leaguer since 1918 to allow only two baserunners in a complete-game one-hit shutout (or no-hitter) over the Yankees.

Knuckleball No-no’s: Had Mike Easler not ruined Candiotti’s no-hitter, it would have been the first AL knuckleball no-hitter since Baltimore’s Hoyt Wilhelm against the Yankees on September 20, 1958*. The last major-league knuckleball no-hitter was in the NL, when Atlanta’s Phil Niekro no-hit San Diego in 1973.

It would’ve been fitting had Candiotti no-hit the Yankees. Entering that game, he was 3-11 on the season. Wilhelm’s no-hitter against New York came during a trying 1958 season. Used as a reliever for most of the year, Wilhelm was 2-10 before throwing the no-no.

*That afternoon, opposing pitcher Don Larsen, author of the only perfect game in World Series history (1956), allowed only one hit in six innings. Orioles catcher Gus Triandos’s 425-foot homer off reliever Bobby Shantz in the seventh won it 1-0. According to Triandos years later: “Catching Hoyt was such a miserable experience, I just wanted to end the game” (Mike Klingaman, “Catching Up With Gus Triandos,” Baltimore Sun, May 5, 2009).

Did You Know?

Coincidence? Maybe not…

When Pat Corrales was managing Cleveland in the first half of the 1987 season, he wanted Candiotti to throw nothing but knuckleballs. That idea didn’t work, as the Candy Man struggled to a 2-9 record.

After Doc Edwards took over as manager at the All-Star break, Candiotti was allowed to use his other pitches along with the knuckler. Edwards’s philosophy was that his pitcher should throw pitches that he felt comfortable with, instead of being forced to throw one pitch repeatedly.

In his second start of the post-Corrales era, Candiotti defeated Texas 4-2 in a game where he relied heavily on fastballs and curveballs. Using those two pitches to get ahead of hitters and throwing the knuckler only in certain situations, he retired the first 12 Rangers before losing the perfect game bid in the fifth inning. He finished with a four-hitter, with the only two runs against him coming on sacrifice flies. It wasn’t a no-hitter, but it was certainly a dominant effort.

This date in history: July 18, 1994 – Candiotti pitches seven innings in relief in New York

Posted by alifeofknuckleballs in (Baseball) Life Ain't Fair..., All About Innings, Baseball History, Dodgers Baseball, Knuckleballs, Oh those blown saves... on July 17, 2022

Here’s a look-back to a Tom Candiotti start from July 18, 1994.

After Candiotti posted a 7-7 record with a 4.12 ERA for the L.A. Dodgers in 1994, skeptics said the veteran knuckleballer was washed up.

In those days, unfortunately, people looked mainly at won-loss records and determined that a pitcher “didn’t know how to win” if he did not post a high number of the left side of that column.

But during that 1994 season, Candiotti was most certainly a valuable pitcher on the Dodgers. And his value was evident during a crucial road trip immediately following the All-Star break, even if it’s been forgotten years later.

At the All-Star break, the Dodgers sat atop the NL West standings, owning a five-game lead over Colorado and a seven-and-a-half-game cushion over San Francisco. A 13-game post-break road trip followed—with stops in Philadelphia, New York, Montreal, and San Francisco—and that was where Candiotti repeatedly bailed out the Dodgers. He gave the club a quality outing each time out when nobody else seemed capable of providing even five innings. He pitched on short rest and in relief.

The bullpen was a disaster during the trip, with Todd Worrell (15.75 ERA), Jim Gott (9.39 ERA), Roger McDowell (9.82 ERA), and Omar Daal (5.40 ERA) all pitching poorly. The starters, meanwhile, were not getting it done either, with Pedro Astacio going 0-2 in two starts with a 22.85 ERA while lasting a total of 4.1 innings. Ramon Martinez was 1-2 with a 5.19 ERA in his three starts. Kevin Gross was 0-2 and 6.11 in three starts. Orel Hershiser pitched just once, getting pounded in San Francisco for five runs in five innings. Ismael Valdez, normally a reliever then, made one start and lasted one-plus inning. Candiotti, however, was not part of the problem, posting a 2.60 ERA in four games and working at least six innings each time.

The Giants would get hot and win 13 out of a 16-game stretch, while the Dodgers would go 3-10 on that road trip and see their lead over San Francisco shrink to only a half-game.

Candiotti pitched on July 15 in Philadelphia, throwing a six-inning four-hitter in a 3-2 victory. He was then called upon on this date, July 18, on only two days’ rest in relief because of the ailing staff.

So, on July 18 in New York, Candiotti was supposed to just be a spectator, but Orel Hershiser had a strained left rib cage muscle and could not start, so Ismael Valdez, a rookie, became the emergency replacement. But Valdez himself had to leave the game after recording just three outs because of a blister.

In came Candiotti on two days’ rest, and he threw seven relief innings of three-hit baseball and the Dodgers won, 7-6, in 10 innings—after Todd Worell inexplicably blew Candiotti’s 6-3 lead in the bottom of the ninth.

Candiotti’s line: 7 IP, 3 H, 2 R, 1 ER, 4 BB, 7 SO. This was on two days’ rest! The only runs off him came on an RBI groundout in the fourth and two errors in the sixth. The Mets’ other run before the ninth inning came off Valdez.

Once again, it was another example of Candiotti coming up big for the club. For the third straight game, a Dodger starter had not lasted past three frames. First, it was Hershiser taking himself out of a game in Philadelphia during his warm-up pitches because of a muscle strain. Ramon Martinez, the emergency starter that day, was clobbered for nine runs in 4.1 innings. The following day, Pedro Astacio allowed six runs in 2.1 frames as the Dodgers lost three of four to the Phillies (with Candiotti getting the lone win). Then it was the Valdez game against the Mets where the rookie had to leave early, and Candiotti provided seven relief innings.

Here is where baseball’s rules concerning wins and losses are flawed. Candiotti worked seven innings and was effective. Worrell gave up three runs on five hits and a walk in his one inning of work, blowing a three-run lead, and yet he was credited with the win after the Dodgers won it in the 10th. Worrell, the most ineffective pitcher on the night, was credited with the victory just because he was “the pitcher of record,” which wasn’t fair.

Candiotti should have gotten the win. And, of course, going back to what I mentioned at the start, people will look at that 7-7 record and deem him a pitcher who didn’t know how to win.

Sure, there were some games during the course of the season where he got roughed up, but there were three other no-decisions in 1994 where he went seven or more innings allowing two earned runs or fewer: April 29 against the Mets, May 20 in Cincinnati, and June 21 in San Diego. That’s four extra wins that he should have picked up, and an 11-7 record vs. a 7-7 mark makes a big difference.

Then, in his next outing after the July 18th no-decision in New York, Candiotti was again outstanding in Montreal—giving up only a sac fly and an RBI single in his seven innings of work—but suffered a 2-0 loss to Jeff Fassero and the Expos. Next up, he took a 1-0 lead into the eighth inning in San Francisco, but ran out of gas as the Giants scored four times in the eighth. It didn’t help that the Dodgers scored just one run against Bill Swift. Take those games in Montreal and San Francisco and say that if he had gotten more support, his record would have been 13-6—not a measly 7-7.

I mean, he just didn’t have any luck. Yes, he ended with a 4.12 ERA. But c’mon. Didn’t Storm Davis win 19 games with a 4.36 ERA in 1989? Jack Morris win 21 games with a 4.04 ERA in 1992? Bill Gullickson, 20 wins in 1991 with a 3.90 ERA?

Tom Candiotti never had a year like that where his team scored a lot of runs for him to be able to rack up a bunch of victories. On this date, July 18, 1994, the Dodgers scored enough runs and Candiotti came through with seven magnificent relief innings. But Worrell blew it.

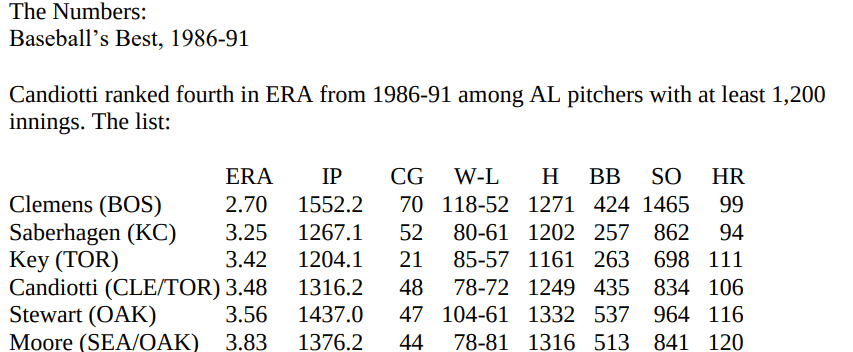

AL’s best pitchers, 1986-91

Posted by alifeofknuckleballs in Baseball on May 2, 2022

When I wrote Tom Candiotti: A Life of Knuckleballs, there was so much information that I included that had to be edited out because of the word-count limit the publisher enforced.

I’d promised to publish some of the “best of the rest” information that didn’t make it into the book. But I haven’t had time–hopefully, though, I’ll get on it and post more.

Here’s one tidbit: Candiotti was the fourth-best pitcher, by ERA, in the AL from 1986-91. Forget the win totals, but look at that ERA and walk totals. And home runs given up.

Compare Candiotti to, say, Mark Langston. Look at how many more walks Langston gave up. Yet Candiotti never received any Cy Young votes or made an All-Star team his entire career. What were the voters and coaches thinking?